Inland Empire (2006) - Best of 2000-2019 Part 4

"My Favorite Films of the 21st Century So Far" series Part Four, and the Fourth of the Five I wanted to highlight as the Best of the Best.

—Spoilers Follow—

INLAND EMPIRE (2006)

Director: David Lynch

Writer: David Lynch

Cinematographer: David Lynch

Music: David Lynch, Angelo Badalamenti

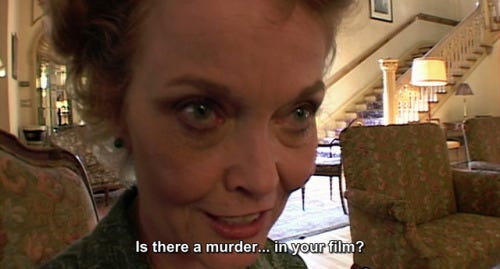

INLAND EMPIRE (tagline: A Woman in Trouble) is a challenging film. Three hours long, shot in 2006 on an already outdated digital camera, and with no clear-cut plot or even characters to speak of, Lynch’s critics could make a good case that this is a mere provocation. A cheap joke at the viewer’s expense which “quickly devolves into self-parody,” as The New Yorker put it.

But it is a masterpiece. Here, Lynch shows us the fragments of a woman’s broken mind manifested in many shards of age-old “woman-in-trouble” Hollywood archetypes. The Woman in Trouble is played by Laura Dern, who in three hours gives us everything from a put-upon working class mom, an aging star gearing up for the big comeback, a tough hick who gives it right back to her abusive husband, southern belle Sue Blue in EMPIRE’s movie within a movie, and a wife subjected to vicious retribution by a maniacally controlling husband. All of which is viewed on a small television set by a weeping Polish girl, credited as “The Lost Girl” (Karolina Gruszka). She is also A Woman in Trouble.

To speak analytically of plot or cinematic technique with regards to INLAND EMPIRE would be a noble effort and a worthwhile one, but I have limited interest in doing so. Upon my last full re-watch a few weeks ago, all I cared about was my absorption of the experience. Coherence cannot be found in storytelling here, at least not in any traditional sense, but in repetition of themes and motifs. I go to the hour and a half point, the mid point of the film, and see the middle class version of Dern (perhaps Sue Blue, the character she is meant to play at the beginning?) eating dinner with her Eastern European husband, supposedly a character in her film named Smithy (Peter J. Lucas). She reveals that she is pregnant, which comes as a shock to him. Later (but also past) events imply that he cannot have children, therefore she has cheated on him. Later on he beats her for this. A Woman In Trouble.

Fast forward eight minutes and Laura Dern, presumably still as Sue, is having a unspeakably off-kilter barbecue with Smithy, who has spilled a tremendous amount of ketchup on his white t-shirt. After Dern tells him where the paper towels are, there is a rapid cut to The Lost Girl in a warmly lit shot reminiscent of the silent picture Norma Desmond shows Joe in Lynch favorite Sunset Boulevard. “Cast out,” she prays, “this wicked dream which has seized my heart.” In old-world Poland, a woman and man both lie dead with bloody stomachs. This is implied to be the result of The Lost Girl cheating on her husband, The Phantom.

Forty-two minutes into the movie there is a scene in which Justin Theroux (the actor version, Devon Birk), who will perform opposite Dern (the actress version, Nikki Grace), as Billy Side in their upcoming film “On High in Blue Tomorrows”, speaks to Nikki’s husband Piotrek Krol. “My wife is not a free agent,” Krol warns Birk, “I don’t allow her that. The bonds of marriage are real bonds. The vows we take, we honor. And enforce them.” A woman in trouble?

As they commence filming, Nikki and Devon show real chemistry on and off set. Tentatively, of course, with the threats of the husband ringing in both their ears. Reality begins truly splitting for Nikki after shooting a passionate love sequence, when she drops her Sue Blue southern accent, face aching with anguish, leans close to Devon (who has not dropped his accent), and whispers “Somethings happened. I think my husband knows about you, about us. He’ll kill you, and me, he’ll…” Suddenly she pulls back, smiling and laughs “Damn! This sounds like dialogue from our script!”

Over and over again, this film repeats scenarios with either slightly or drastically different contexts. The first pieces of the film came together in 2002 when Lynch put Naomi Watts, Laura Harring, and Scott Coffey in life-sized rabbit suits for a series of online shorts titles Rabbits (2). Then, he met up with Laura Dern and asked her to read some dialogue he’d written while sitting opposite Erik Crary (Here’s some of it) while he filmed on his PD-150. Longtime assistant Jay Aaseng said that “after we were finished and Laura had gone home, David was having a smoke in the painting studio and he was really excited. His eyes were just lit up. He looked at us and said, ‘What if this is a movie?’ I think that’s when INLAND EMPIRE was born.” (3) Lynch himself says of the project that “I got another idea but I didn’t know how it related to Laura’s scene. I liked it, though, so I shot it, and a little bit later I got another idea didn’t relate to either of the two things I’d shot. Then I got a fourth idea that unified everything, and that started it.” (4)

I include all this in an attempt to make the point that INLAND EMPIRE is not some great puzzle waiting to be pulled apart. There are explainer videos and wiki pages that give satisfactory interpretations of its symbolism and some believable enough linear reorganizing. But what’s the point? Okay, now I know who’s who and what’s what and when’s when, but isn’t that all so god damn boring compared the the sheer visceral and emotional impact these scenes deliver? You can skip to any moment in this movie and watch it and see something vital, delirious, and bizarre. The story of INLAND EMPIRE is storytelling itself! From old-world Poland to present day Los Angeles we watch the same tropes, themes, and motifs fold in on themselves over and over. Nikki plays Sue in an adaptation of a polish folk tale about “The Lost Girl” and becomes all three at once, telling the same story over and over again. Becoming Sue and receding into the narrative as her “real life” begins to mirror “fiction” far too closely, she escapes finally by shooting The Phantom as her own warped clown (actor) face is projected over his. Freedom from her own ego, or self-conception, or public image, or maybe the personification of women warped and mutilated by men.

Draw the conclusions you will, but one thing I can comfortably claim is that by this point, The Woman is No Longer in Trouble. Nikki enters the room of The Lost Girl, a sort of limbo in which she has watched the events of the film unfold, kisses her, and fades away. The Lost Girl seems to reunite lovingly with her husband (Smithy) and son as Nikki stands in what may be The Rabbits apartment, inter-cut with a blindingly blue projector’s light. I believe this to be a statement by Lynch on the ability of film to create dreams, and Nikki is now placing herself back at the beginning of the film, serene in her blue dress. On High In Blue Tomorrows. Cut to black.

INLAND EMPIRE is David Lynch’s definitive statement on movies. It is self-consciously a film, and deals extensively with the production and particularities of creating in that medium. It is about the experience of watching movies and the projection of oneself onto a character, and the absorption of a character into an actor. The series of shots that comprise INLAND EMPIRE are bound only by audio/visual coherence, repetitive scenarios, the performance of Laura Dern, and Lynch’s uncanny ability to put every piece in precisely the right place. So much of the tremendous potential offered by film are present here; there is simply no other medium that could conceivably accommodate it. Lynch has said that EMPIRE will be his last film, and that makes sense. The end credits are his grand finale.